As I wrote last week, James Webb Young once described the creative process as using the “production line of the mind” to generate ideas. This metaphor for the creative process is useful because it specifies a mental technique that can be learned. The technique is not esoteric, mysterious, or romantic, but rather consists of a few simple principles and methods that you can train yourself to use in your daily life. Young’s enduring insight is that the “production line of the mind” is the source of all ideas.

But what is an idea? Steve Jobs described it as nothing more than a connection between two previously unconnected things. Young defined an idea as an insight, or a fresh new combination or relationship.

If this sounds a bit mechanical or simplistic, fret not. David Ogilvy—the inspiration for one of television’s most famous “creatives,” Don Draper—explains coming up with ideas as: “a groping experimentation […] governed by intuition, hunches, and inspired by the unconscious” (42).

I like Young’s metaphor because it promises a certain level of systematicity to the creative process. But, like Ogilvy, Young came to his understanding of creativity from the business world. Perhaps that language—and all that it implies—isn’t your cup of tea. In fact, you need not buy into the “assembly line” metaphor at all! For one thing, it turns out a lot of other people have had the same fundamental insight as Young, a few others of which I introduced in my last post. The similarities between them are fairly apparent, but synthesizing them here serves my purpose to present another, more playful, metaphor of my own: The Rock Tumbler.

***

The three models of the creative process I shared last week were: Mihaly Csikszentmihaly’s “Classical” model, James Webb Young’s “How to Have Ideas,” and Graham Wallas’s “Dance of Delicate Osmosis between the Conscious and Unconscious. They each have four or five “steps” or phases, and follow the same basic outline.

First you begin by consciously learning new things and gathering materials to work with according to your natural curiosity in a range of topics. In the classical model this is called “Preparation,” in “How to” it is subdivided into the two distinct steps of “Gather raw material” and “Digest the material,” and in the “Dance,” it is described as “readying your mental soil for sowing.” Importantly, this is a conscious process of research, planning, browsing, and following your inclinations. This ought to be done for its own sake. It’s fun to find novelty in the world!

Second you let what you’ve learned and gathered marinate in your subconscious. Dr. C calls this “Incubation,” Young calls it “Unconscious processing,” and Wallas calls it “mental mastication.” The point is that, for a time, we do not will ourselves to generate ideas; we take our mind off the material we’ve gathered and go do something else, so as to “make no effort of a direct nature.” According to Young, the best thing to do is to turn to something that stimulates your imagination and emotions—music, theater, film, poetry, fiction, art, dance, and so on.

Third you wait for insight to emerge. It may seem outrageous to the skeptic, but creatives know that connections and insights will emerge on their own. Csikszentmihaly describes it as “allowing ideas to call to each other on their own,” through what Wallas calls involuntary mind events, characterized by illumination of a serendipitous alignment or association. You might also, as Young does, consider it to be no more or less than: the moment of “Aha!” or “Eureka!"

Fourth you either immediately manifest the insight or capture it for later. Here, you either make something (a sculpture, a sketch, a melody, a flavor, and so on) or write something down. This is best done as soon as possible, and, if putting off actualization until later, the note ought to be written in as much detail as possible.

Fifth you evaluate and elaborate the insight, judging whether it is any good or not, and building on it if it passes muster. Csikszentmihalyi identifies two phases at this stage in the process. The first—evaluation—concerns whether the idea or insight makes sense, whether it is valuable, whether it is novel, trivial, profound, or otherwise. The second—elaboration—relates to developing the idea, getting feedback, refining, focusing, and presenting the idea. Young challenges us to ask: is it useful? Is it generative? This phase feeds directly back into the first: your new insight can be one of the raw materials you have gathered to feed back into the process.

The first and second phases are the most critical. Without them, the other three cannot happen. But, it is useful to have this framework, because it matches the process by which you play with a rock tumbler.

Playing with a rock tumbler involves all of the stages explained above and provides a simple shorthand to describe the different components creative process. It has allowed me to recognize when and how I’ve become stuck or “blocked” by giving me a language to describe what is—or isn’t—happening with my process.

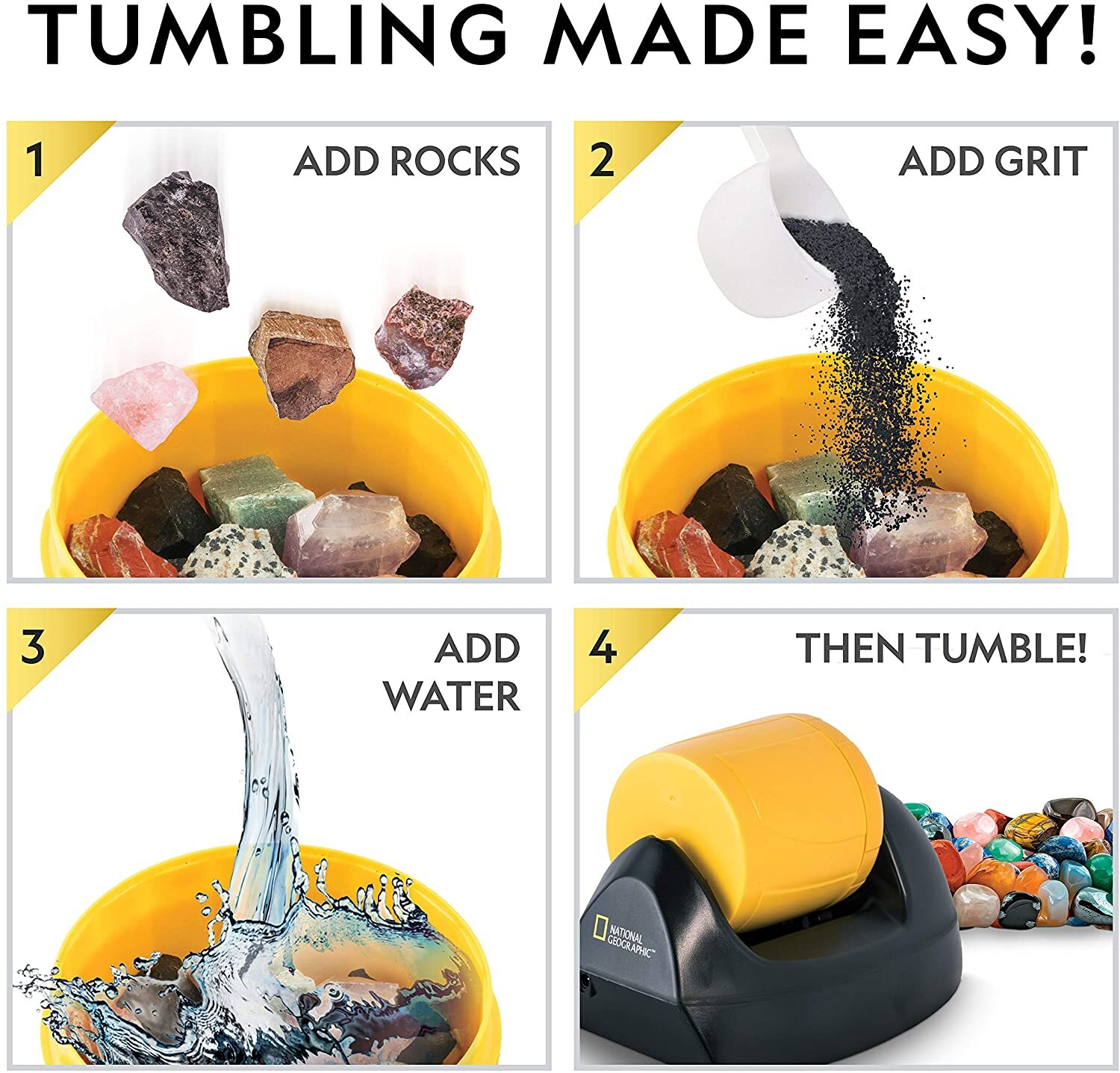

Preparation: collect your rocks and select those to tumble, add water and grit,

Incubation: turn the tumbler on, go do something else while it works,

Insight: turn the tumbler off, open up to inspect,

Capture: take a look at your rocks, are they polished enough?

Elaborate: select the rocks you like, make something with them

The rock tumbler metaphor is useful for me because it affords the identification of distinct flow activities that comprise the “creative process.” I know, for example, that certain times of the day and week are better for me to consciously choose to do the activities of Preparation and Elaboration. I also know that if I do not schedule enough time for the kinds of activities that allow me to “mentally masticate,” I will begin to get frustrated and antsy. But also, if I let the first four steps go buck-wild without doing enough elaboration, I get easily overwhelmed by the amount of things I want to do in comparison to the amount of time I realistically have to put toward them.

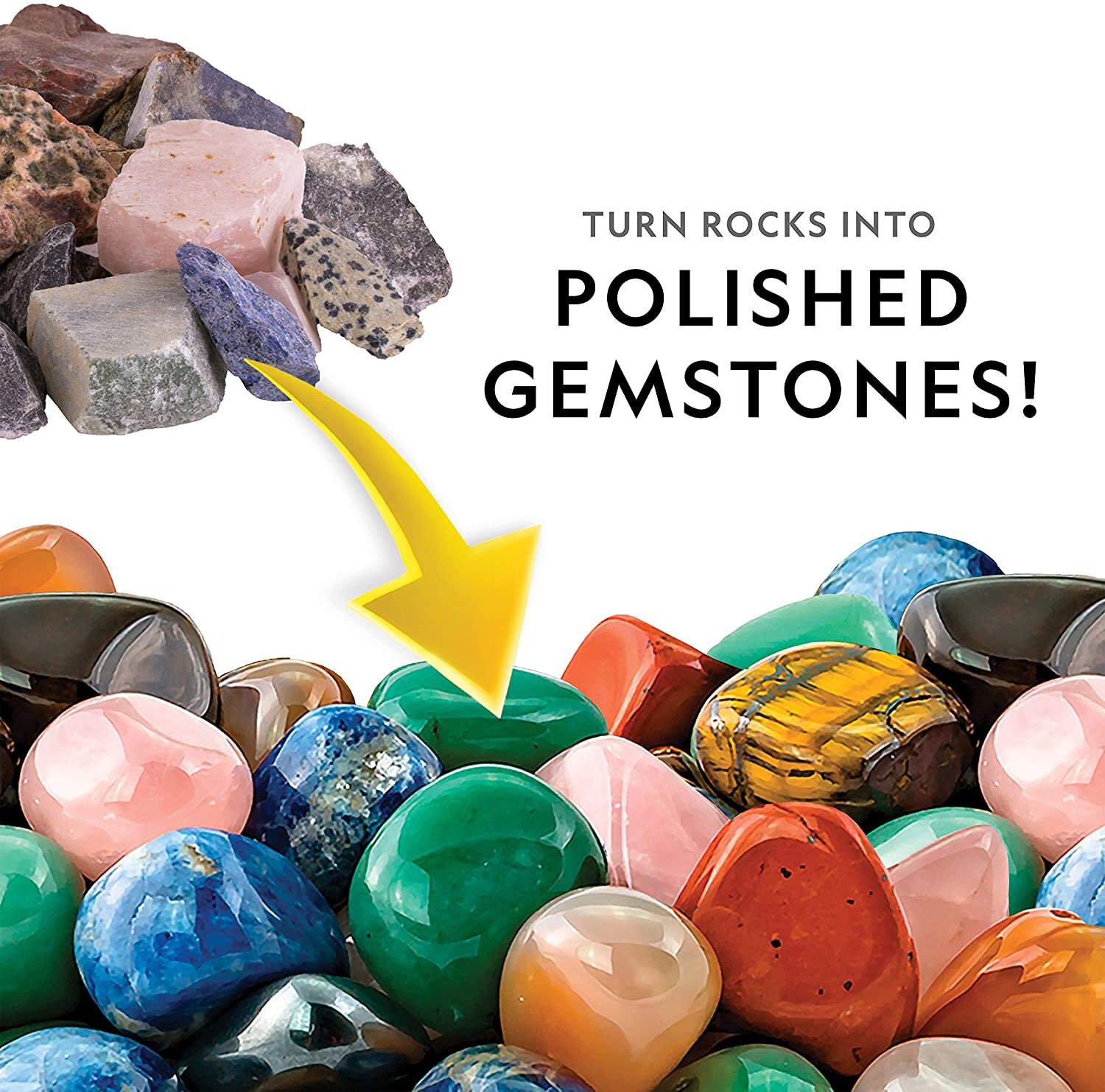

The metaphor also serves some useful diagnostic functions for when things aren’t going so well. It helps to know that sometimes you put rocks in the tumbler and they turn out to have been clods of hard dirt, or simply have no luster or interesting properties once polished, and that’s okay. You get duds, ideas that don’t go anywhere and insights that turn out to be half-baked or derivative. This is a feature of the system, not a bug. But if you don’t put rocks in the tumbler, you won’t get any gemstones to make jewelry with.

It is also true that, if you are unwell and/or not properly rested, the tumbler doesn’t seem to work quite right. It takes longer for the rocks to become smooth, if they ever do at all. When you start to notice yourself not having many ideas or generating insights, you can ask yourself: have I not put enough promising rocks into the tumbler, have I not ensured that the crank-shaft is working smoothly, or—God forbid—both? You may also notice that you struggle with or no longer enjoy stringing together certain kinds of beads, so to speak. You can then ask yourself, is this a problem with the beads themselves? Maybe you’re tired of a certain color, but you could also have lost interest in bracelets—either way, the solution becomes easier to see when you have this heuristic model to describe the problem that you’re having.

***

I’ll have a lot more to say about the diagnostic power of the Rock Tumbler metaphor for the creative process in future essays, but for now, I recommend trying Young’s technique. It has worked for me for several years, and all the more so since I began to think of it more playfully using the Rock Tumbler metaphor. My understanding and use of Young’s technique was, for a long time, closely linked to my desire to be more productive in my work. While the “assembly line of the mind” can certainly help you be more productive, the machinery that all the models of the creative process describe are all the more effective if they are pursued for a different reason: enjoyment. Being creative is supposed to be fun!

So, what’s it going to be for you? My creative life has become so much more fulfilling in the months since I remembered the point of it all. If you want a concrete thing to try out to test Young’s technique and see if it works for you, give this exercise from Julia Cameron a try! Run with whatever seems most fun and doable.

“If I didn't have to do it perfectly...”

Get a piece of paper and number alternating lines, one through ten.

On the line numbered one, write out "If I didn't have to do it perfectly, I would…" followed by whatever comes to mind.

Do it again for lines numbered 2 through 10 in quick succession. In fact, you should aim to do this exercise as quickly as possible. Pro Tips: “Don't over think, write whatever comes to mind, no matter how odd/non-sensical/boring/silly/irrelevant/relevant/scary it might seem.”

Let the list sit for a while before coming back to it. Read it over, take note of any patterns or strong reactions. What is most irresistible? What seems like the most fun?